We’ve all met them—and sometimes been them: the person who explains a topic with supreme certainty, only to reveal they don’t understand the basics. Psychologists call this the Dunning–Kruger effect: a cognitive bias where people with low skill or knowledge in a domain overestimate their ability because they don’t yet know enough to see their own mistakes.

The Short Version

- What it is: A gap between confidence and competence caused by missing metaknowledge (“knowing what you don’t know”).

- Why it happens: Early exposure gives you just enough surface fluency to feel expert—without the depth to detect errors.

- What it looks like: Strong opinions, weak grasp of fundamentals, and resistance to feedback.

A Quick Story

Alex watches a handful of videos about cryptocurrency, makes two lucky trades, and concludes the whole thing is easy. Warnings about risk management? “FUD.” Alex starts giving advice, dismissing pros as “overcomplicating it.” A month later, volatility wipes out most of the gains. The market didn’t humble Alex—the unknown unknowns did.

The Cognitive Mechanics

- Low knowledge → low error-detection. If you lack core concepts, you can’t accurately judge your own performance.

- Fluency illusion. Fast, smooth explanations feel like mastery, even when they’re shallow.

- Early wins inflate confidence. Random success masquerades as skill.

- Feedback avoidance. Overconfidence filters out corrective signals, protecting the illusion.

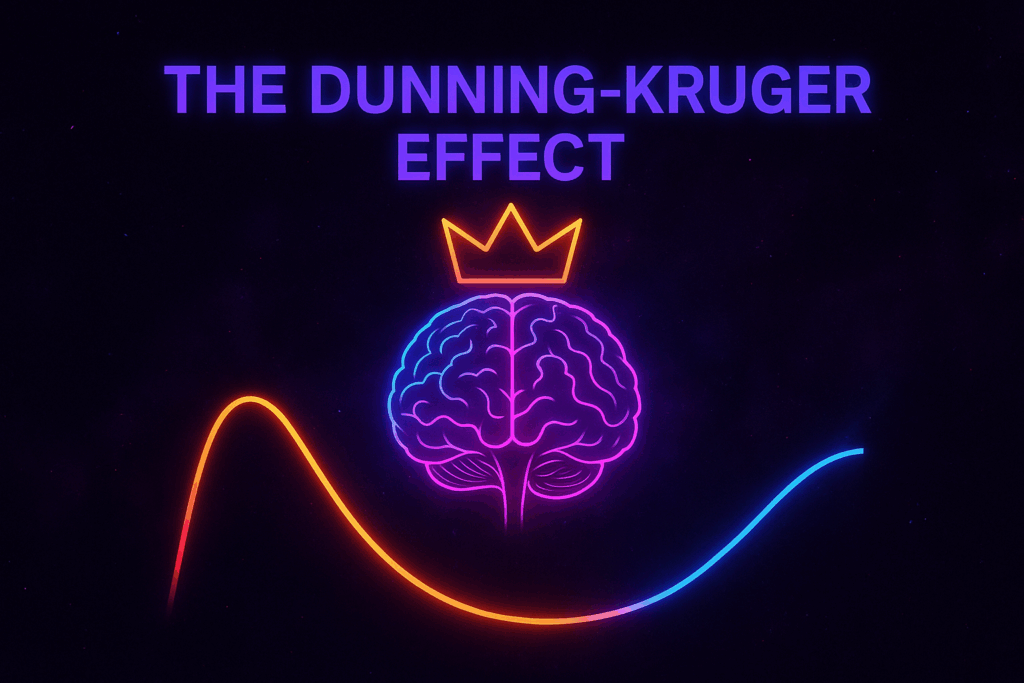

The Curve You Feel (Not See)

- Stage 1: Peak of Mount Stupid. Rapid confidence from a small knowledge base.

- Stage 2: Valley of Realization. Exposure to complexity collapses certainty.

- Stage 3: Slope of Calibration. Skill and humility grow together.

- Stage 4: Plateau of Sustainable Competence. Quiet confidence, precise claims, clear limits.

How to Spot It (In Yourself and Others)

- Overprecision: Exact predictions on complex, uncertain systems.

- Jargon padding: Buzzwords without operable definitions.

- No baselines: Can’t explain fundamentals or first principles.

- Feedback allergy: Interrupts corrections, moves goalposts, or attacks the messenger.

- One-lesson mastery: Reads a summary, claims expertise.

The Mirror Test (Self-Check)

Ask yourself:

- Can I teach the basics clearly, step-by-step, to a beginner?

- What would change my mind? (Name a falsifiable condition.)

- What are the edge cases? (List three where your idea could break.)

- Who disagrees that I respect, and why might they be right?

- What metric or outcome would count as failure?

If you can’t answer briefly and concretely, your confidence may be outpacing your competence.

Dunning–Kruger vs. Impostor Syndrome

- Dunning–Kruger: Low skill, high confidence. Problem: invisible gaps.

- Impostor Syndrome: High skill, low confidence. Problem: invisible strengths.

Both distort reality. One needs humility and structure; the other needs evidence and self-trust.

Practical Antidotes (Fast, Repeatable)

- Install baselines. Before opinions, write down the core definitions, units, and constraints. If you can’t define it, don’t opine on it.

- Set error budgets. Decide upfront how wrong you’re allowed to be and what triggers a reset.

- Use pre-mortems. “If this fails in 90 days, why?” List the top three causes; design counters now.

- Run small stakes. Pilot with reversible decisions. Scale only after measured success.

- Feedback contracts. Ask a domain expert for one brutal page of critique. Don’t defend—annotate and fix.

- Track calibration. Keep a log of predictions with confidence levels. Compare belief vs. reality monthly.

- Red-team your ideas. Assign someone (or your future self) to attack assumptions from first principles.

Signals of Real Competence

- Scoped claims: “This holds under X conditions; it breaks under Y.”

- Plain language: Jargon only when necessary, with definitions.

- Transparent uncertainty: Confidence intervals, not absolute pronouncements.

- Evidence trails: Data, methods, and reproducibility.

- Adaptive learning: Incorporates new facts without ego collapse.

Why This Matters (Beyond Ego)

Overconfidence is costly: bad trades, failed projects, broken trust, and missed learning cycles. The Dunning–Kruger effect isn’t a character flaw—it’s a stage on the path to mastery. The goal is not to never be wrong; it’s to shorten the distance between being wrong and realizing it.

A Simple Ritual to Stay Honest

- Before: State your hypothesis, success metric, and kill switch.

- During: Log deviations and decisions in real time.

- After: Do a no-excuses postmortem. Publish the lessons (even just to yourself).

Confidence is earned by surviving contact with reality. Competence is the trail of corrections you’re willing to make along the way. When you pair both, you exit the illusion—and enter growth.